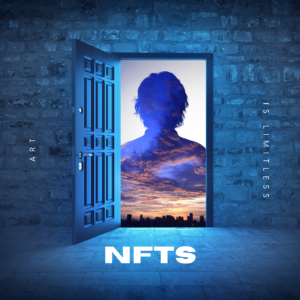

The subject matter of copyright is an immaterial literary or artistic work that must be distinguished from its material support (a CD, a book, a USB key, etc.). The purchaser of a material object that incorporates a work does not necessarily have the copyright on this work and therefore cannot use it in a way that would infringe these rights.

Examples :

I buy a CD of Hooverphonic. The work consists of the songs recorded on this CD. The medium of the work is the CD.

My ownership of the CD does not authorize me to make any use of the work that is subject to copyright, such as making copies or posting the song on the Internet.

The owner of a painting by Magritte has no copyright on the work. He could not therefore decide to make photographs of it and distribute them, despite being the owner of the painting. Because on this occasion, he would be making copies of the work, an act subject to copyright.

Read: What is copyright protection?

As explained above in the section on copyright, the creator/vendor of NFTs has every interest in protecting himself with specific contractual clauses or terms and conditions relating to his intellectual property.

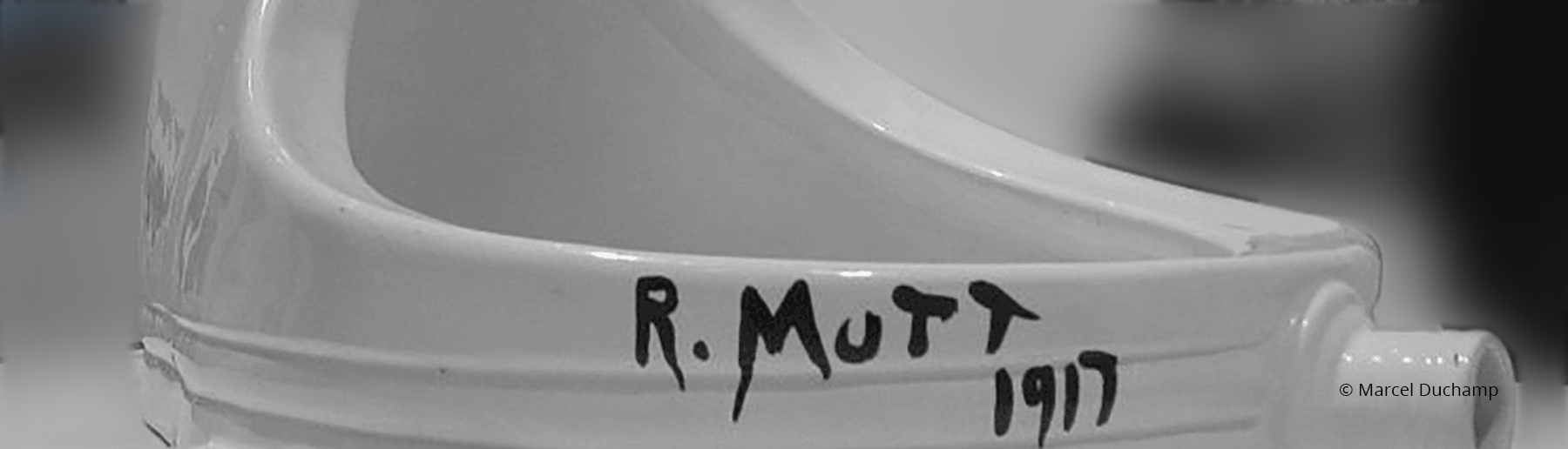

The owner of a plastic or graphic work, an NFT, has only these rights provided by the Code of Economic Law:

The right to exhibit the work

“Art. XI.173. CDE: “Unless otherwise agreed, the transfer of a work of plastic or graphic art entails for the benefit of the purchaser the transfer of the right to exhibit it as is, under conditions not prejudicial to the honor or reputation of the author, but not the transfer of the author’s other rights.

Unless otherwise agreed or customary, the transfer of a work of plastic or graphic art entails the prohibition of making other identical copies.”

The purchase of a work of art does not authorize its owner to distribute it.

The right to exhibit a work can therefore be revoked since this provision is suppletive (“Unless otherwise agreed“).

This right must be interpreted in such a way that the owner only has the right to exhibit it as it is. He cannot modify it in any way (this would be an attack on the integrity of the work). Finally, it should be specified that the right to exhibit the work must not be confused with the economic rights of rental and loan.

The artist’s commitment not to make other copies of the work

The second paragraph of Article XI .173 CDE states, “Unless otherwise agreed or customary, the assignment of a work of plastic or graphic art carries with it the prohibition of making other identical copies.”

The control of this prohibition is particularly easy for NFTs. The specificity of a cryptographic token or NFT, which represents a digital object such as an image, a video, an audio file, to which a digital identity is attached, is precisely to allow its authentication thanks to the protocol of a blockchain which gives it its first value.

Non-fungible tokens are therefore not interchangeable and their originality and rarity are guaranteed by the technologies of their creation, while the law prohibits the making of other identical copies.

How do I authenticate my NFT? Read: How NFTs Are Tracked and Verified.

EXCEPT AS OTHERWISE AGREED OR USED, THE TRANSFER OF A WORK OF PLASTIC OR GRAPHIC ART IMPLIES THE PROHIBITION TO MAKE OTHER IDENTICAL EXEMPLES.

The parties can derogate from this rule, so that once again the drafting of a “sui generis“ agreement can prove to be value-creating, especially in the long term.

The parties can derogate from this rule, so that once again the drafting of a “sui generis“ agreement can prove to be value-creating, especially in the long term.

Who of the sale of ONE NFT and the possibility – included in a smart contract – to “print” (think of the old lithographs) X copies if, for example, each copy reaches at least such amount on an exchange platform? The technologies of the blockchain allowing easily the exercise of the right of resale, these contractual variations on the number of reproductions have no limits but the imagination of the parties.

As for the respect of the integrity of the work

NFTs being digital works easily modifiable by digital artists, the articulation between modification of the materialized work (NFT) and copyright is obvious.

The respect of the work by the owner

The owner must respect at all times the right to the integrity of the work that the author retains despite the transfer of ownership of the object as such.

This right is particularly powerful since the author does not have to justify any prejudice, which is an important nuance compared to the principles established in civil law and to which jurists are accustomed.

Nevertheless, as the Court of Appeal of Brussels reminds us, the right to integrity is not absolute and finds its limit in the abuse of right of its holder.

Case law and doctrine have long been concerned with the consequences of modifications made by a second artist on the work of a first:

“Finally, the work of art, victim of time, can be the object of a restoration. Even if the qualified restorer must respect the qualities of the original creation, the restored work becomes a retouched work of which the initial author can seem partially evicted since it is not exclusively of his hand. We add that in certain cases, the original work is so retouched that we can no longer claim to be confronted with it, but with a new object..

These factors are all the more exacerbated when we read them in the light of the law applicable in favor of the artist, namely copyright protection, and in particular the right of the artist to prohibit any mutilation of his work. The news of the last few years offers us an excellent illustration with the amusing restoration of the “Ecce Homo”, work of the little known artist Elías García Martínez and property of the church of the village of Borja, in Spain. As a reminder, Cecilia Giménez, a resident of the village, undertook the restoration of the work in question. Surprising result! The artist himself would now be unable to recognize his creation. One could in a way speak of an authentic work covered by another work that turns out to be, in the end, original in the sense of copyright.

From then on, the situation can be summarized as follows: the work of art is then partly the fruit of the work of a third person, the pupil, the collaborator, the restorer and is no longer the exclusive work of the artist, which makes the task of authentication all the more complex.

To return to our example, from a legal point of view, one of the rights of the author is the respect of the creation and its integrity. During the restoration of “Ecce Homo”, there is no doubt that this right was not respected. However, since copyright has a limited duration, the restorer was not worried, as the rights were extinguished.

Copyright applicable or not, the fact remains that the failure of a restoration causes prejudice to the owner of the work who sees the value of the work more or less strongly reduced. If a person causes harm to another person, he must repair it, for example by paying damages through his extra-contractual liability.”

Extracted from: Alexandre PINTIAU – L’authenticité- Patrimoine et œuvres d’art – Questions choisies – 1re édition 2016 – Larcier – P. 150.

The purchaser of an NFT must therefore respect its integrity and may not, unless otherwise agreed, modify it, in whole or in part.

As for the modification or destruction of the work

The abusus is one of the attributes of the right of ownership, the right to dispose of one’s property, whether it be the legal disposition of one’s property by alienation (sale or gift) or material disposition by destruction. The abusus is a real right in the sense that it is exercised on a thing.

The abusus is thus held by the owner of the NFT who has acquired the “thing”, being the digital work to which a digital identity is attached. He has the right to sell or destroy the NFT.

The conflict is immediately apparent from the fact that the artist retains all of his copyright even in the event of its sale, including the right to object to any modification or alteration of the work (Article XI. 165, § 2 CDE).

One is the right of the owner on the basis of the Civil Code and the other one is one of the moral rights of the author fixed in the Code of Economic Law. How can we distinguish between them? The doctrine summarizes the decisions relating to such a case by the principle of “balancing”, the judge having to decide in favour of one or the other party, according to the facts of the case.

It will again be necessary to contract with the creator/seller of the NFT, adaptations or variants that the buyer wishes to make to the work.

As for the right of resale

BLOCKCHAIN technology allows to integrate in a SMART CONTRACT the remuneration that the creator/seller of NFT will receive at each subsequent resale. Smart contracts are contracts that are automatically executed when certain conditions are met.

It is therefore once again necessary to draft the clauses relating to these subsequent and future remunerations, their amount or method of calculation (as a rule degressive according to the amount of the sale), their method of collection and payment to the author, their possible exceptions in terms of duration or amount, the possible prohibitions of resale (for example below a certain threshold,…), the methods of settling disputes, the competent jurisdiction,… The autonomy of the will still plays a predominant role here and the parties benefit from formalizing and contractualizing their agreement.

SMART CONTRACTS allow for automatic revenue collection for creators/sellers of NFTs on the resale of their work.

It remains to articulate these contractual provisions with the imperative legal regime resulting from a European circular: the droit de suite.

Conditions of application of the right of resale

The matter concerning the resale right was unified in 2001 by a European Directive 2001/84/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 September 2001 on the resale right for the benefit of the author of an original work of art.

The first recitals of the Directive define the resale right and set out the principle:

- In the field of copyright, the resale right is the non-transferable and inalienable right of the author of an original work of graphic or plastic art to be economically interested in the successive resales of the work concerned.

- The resale right is a right of frugal essence that allows the author-artist to receive remuneration as the work is successively disposed of. The object of the resale right is the material work, i.e. the support in which the protected work is incorporated.

- The resale right aims to ensure that authors of graphic and plastic works of art benefit from the success of their creations. It aims at restoring a balance between the economic situation of the authors of graphic and plastic works of art and that of other creators who benefit from the successive exploitation of their works.

- The resale right is an integral part of copyright and an essential prerogative for authors. The imposition of such a right in all Member States responds to the need to ensure an adequate and uniform level of protection for creators.

Here is the provision in Belgian law:

“Art. XI.175. of the Code of Economic Law: 1 § 1. For any act of resale of an original work of art in which professionals of the art market intervene as sellers, buyers or intermediaries, after the first transfer by the author, an inalienable resale right shall be owed to the author by the seller, which may not be waived, even in advance, calculated on the resale price.

For the purposes of this section, “original work of art” means works of graphic or plastic art such as paintings, collages, paintings, drawings, engravings, prints, lithographs, sculptures, tapestries, ceramics, glassware and photographs, provided that they are creations executed by the artist himself or herself or copies considered as original works of art.

Copies of works of art covered by this section, which have been executed in limited quantities by the artist himself or under his responsibility, shall be considered original works of art for the purposes of this section. Such copies shall normally be numbered or signed, or otherwise duly authorized by the artist.

§ 2. The resale right does not apply , however, to an act of resale when the seller has acquired the work directly from the artist less than three years before the resale and the resale price does not exceed 10,000 euros. The burden of proof of compliance with these conditions lies with the seller.

§ 3. The resale right shall belong to the heirs and other successors in title of the authors in accordance with Articles XI.166 and XI.171.

§ 4. Without prejudice to the provisions of international conventions, reciprocity shall apply to droit de suite.”

The NFT being a graphic or plastic work and in principle original, is thus subjected to the right of continuation if the sale intervenes by professionals of the art and the resale price exceeds 2000 euros without VAT.

“Art. XI.176. of the Code of Economic Law: “The resale right is calculated on the sales price before tax, provided that it is at least 2,000 euros. In order to eliminate disparities that have negative effects on the functioning of the internal market, the King may modify the amount of 2,000 euros without, however, being able to set an amount higher than 3,000 euros. The amount of the resale right is fixed as follows:

– 4% for the portion of the sale price up to 50,000 euros;

– 3% for the portion of the sale price between 50,000.01 euros and 200,000 euros;

– 1% for the portion of the sale price between 200,000.01 euros and 350,000 euros;

– 0.5% for the portion of the sales price between 350,000.01 euros and 500,000 euros;

– 0.25% for the portion of the sale price exceeding 500,000 euros.

However, the total amount of the fee may not exceed 12,500 euros.”

The beneficiary is logically the artist. It is an inalienable right, without losing sight of the fact that from the death of the author, his heirs and other beneficiaries benefit from it for 70 years.

In essence, the auction house, the gallery owner, the art dealer and the intermediaries allowing a seller to come into contact with a buyer meet this condition (Alexandre PINTIAU – Le point sur les récents changements en matière de droit de suite- Patrimoine et œuvres d’art – Questions choisies – 1re édition 2016 – Larcier – P. 208.).

Can we consider NFT exchange platforms as qualified intermediaries to recognize the exercise of resale rights by selling artists? Do the general conditions of these online sites reveal such an intention? Are they in fact modern art galleries that should naturally be subject to the same regulations?

What is an art gallery?

An art gallery is generally a place, public or private, especially arranged to develop and show works of art to a public of visitors, within the framework of temporary or permanent exhibitions. The public art gallery may be integrated into an institutional structure such as a museum, or it may be an autonomous exhibition space. The private art gallery, more particularly intended for the sale, is also a place of exposure and meeting, the “window” of the art dealers.

The works exhibited generally come from the plastic arts, they are hung: paintings, drawings, photographs, or placed on the ground: sculptures. But we can also find works of all kinds, like old or contemporary furniture.

The recent development of the Internet has allowed the creation of virtual “art galleries”, removing geographical constraints.

Wikipedia – Art gallery

Single platform for the management of the right of resale

When codifying the CDE, the Belgian legislator integrated these aspects by providing for the creation of a single platform in charge of the management of the droit de suite. Article XI . 177 CDE provides that for the purpose of managing droit de suite, a single platform is created by the management companies that manage droit de suite. The declaration of resales referred to in Article XI.175, § 1, and the payment of the resale right shall be made via the single platform.

The NFT exchange platforms are for us “professionals of the art market intervening in the resale as sellers, buyers or intermediaries” and are therefore obliged to notify the sales to the unique platform.

“§ 1. For resales made in the context of a public auction, the art market professionals involved in the resale as sellers, buyers or intermediaries, the public officer and the seller are jointly and severally required to notify the sale to the single platform within one month of the sale. They are also jointly and severally liable to pay the duties due via the single platform within two months of the notification.”

For resales that are not carried out in the context of a sale by public auction, including sales that have given rise to the application of Article XI.175, § 2, the art market professionals involved in the resale as sellers, buyers or intermediaries and the seller are jointly and severally liable to notify the sale to the single platform within the time limit and in the manner set by the King. They shall also be jointly and severally liable to pay via the single platform the duties due within two months of the notification.”

The platform is available here: www.resaleright.be.

eResaleRight | Tel : +32(0)2/725.11.75 | contact@resaleright.be

Who has to pay the resale right?

Article XI.175. CDE provides: § 1. For any act of resale of an original work of art in which professionals of the art market intervene as sellers, buyers or intermediaries, after the first transfer by the author, an inalienable resale right is due to the author by the seller, which cannot be waived, even in advance, calculated on the resale price.

Since the judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (C.J.U.E, February 26, 2015, aff. C41/14), it is in accordance with the Directive to agree by agreement that a defined party will bear the cost of the resale right alone, to the discharge of the seller notwithstanding the transpositions into national law .

“European auction houses will undoubtedly seize this opportunity and will not fail to adapt their general conditions accordingly. Candidate buyers should therefore take this possibility into account because, in concrete terms, the price set by the final auction could be increased by (1) the auction house’s costs (as in the past) and (2) the amount corresponding to the droit de suite to be paid, if applicable, subject to article 178 analyzed above.”

As for the originality of the works

It appears from the comments of the doctrine that copyright consists of a set of legal prerogatives recognized to the creator of a work, allowing him on the one hand, to ensure the respect of the intellectual integrity of his work and on the other hand, to ensure its economic exploitation.

Indeed, Article XI.165, § 1 of the Code of Economic Law (hereinafter “the Code”) states that:

“The author of a literary or artistic work has the sole right to reproduce it or to authorize its reproduction, in any manner and in any form, whether direct or indirect, temporary or permanent, in whole or in part. (…)

The author of a literary or artistic work has the sole right to communicate it to the public by any means (…).

The author of a literary or artistic work has the sole right to authorize the distribution to the public, by sale or otherwise, of the original of his work or copies thereof.

The Code does not list the categories of protected works or describe their components.

Contrary to certain preconceived ideas, copyright is by no means confined to the artistic or literary domain and, consequently, the notion of work must be understood in a broad manner.

Literary work does not only refer to works of “literature” in the cultural and aesthetic sense of the word (D. VOORHOOF, in F. BRISON & H. VANHEES (dir.), Hommage à Jan Corbet, Larcier, Gand, 2e éd., 2008, p.51) .

The courts and tribunals have assimilated to literary works a technical work (Brussels, February 27, 1954, T.J., 1954, p. 278.), a video game manual (Brussels, November 9, 1972, T.J., 1973, p. 463.), a user’s manual (Civ. Liège, October 2, 1992, T.J., 1993, p. 342.) or a scientific course in genetics (Brussels (9th ch.), April 11, 1997, A&M, 1997, p.265.).

In order for a creation and/or work to benefit from copyright protection, two conditions must be met: it must be original (and put in a form that reflects the will of its author to communicate it).

The objective of copyright is to encourage creation, by guaranteeing to those who devote themselves to it the possibility of making this economic activity viable, even profitable, and to allow the diffusion of creation to the public by associating the creators.

NFTs can thus serve as unique and modern solutions to protect original works of any kind with the help of “smart contracts” written in the blockchain.

Thus, the intellectual property of the works is guaranteed and easily controllable, while the creators can collect revenues throughout the life cycle of their works.

NFTs can be added to the protection regime of trademarks (®), patents and in a general way of Copyright (©) and open the world to explore virtual universes (metaverse).

As with any transaction, artists and buyers/sellers of NFTs will pay particular attention to the applicable contractual terms and conditions.