In economic terms, the work of the mind is a non-exclusive good, i.e. it is not possible to prevent an agent from using it, and a non-rival good, i.e. its utility does not decrease if the number of users increases. It therefore has the qualities of a public good.

Conversely, the physical medium through which the work is communicated is a rival and exclusive good. For example, in a theatrical performance, the dramatic work itself is a public good, while the seats rented by the audience are rival and exclusive goods.

However, the work, creation of the spirit – immaterial thing thus -, is concretized most often in the matter.

(…)

Most often, the literary work is put down on paper, the musical work pressed or engraved on discs, the architectural work translated into stone… To tell the truth, the intensity of the link between the creation and its support is variable. If the distinction appears relatively easy in literary or musical matters, it is less obvious when one considers a plastic work realized in a single copy.

The link between the creation and its support is then so close that one does not hesitate to use the same term of “work” to designate the one or the other. It is however imperative, legally, to always distinguish the work creation from the work support or, to use the consecrated terminology, the corpus mysticum from the corpus mechanicum. It is because it is indeed a question of two distinct things, objects of different rights: the right of author for the first, that of property for the second (1). What is more, the two rights are acquired according to different modalities and the transfer of one does not necessarily imply the transfer of the other (2). Their owners will therefore often be different and their interests will not always converge. However, even if copyright has the work as its direct object, its exercise often reflects on the medium and, conversely, the acts performed on the material thing by its owner can have repercussions on the work carried by the latter.”

The link between the creation and its support is then so close that one does not hesitate to use the same term of “work” to designate the one or the other. It is however imperative, legally, to always distinguish the work creation from the work support or, to use the consecrated terminology, the corpus mysticum from the corpus mechanicum. It is because it is indeed a question of two distinct things, objects of different rights: the right of author for the first, that of property for the second (1). What is more, the two rights are acquired according to different modalities and the transfer of one does not necessarily imply the transfer of the other (2). Their owners will therefore often be different and their interests will not always converge. However, even if copyright has the work as its direct object, its exercise often reflects on the medium and, conversely, the acts performed on the material thing by its owner can have repercussions on the work carried by the latter.”

Read: Vanbrabant, B., « Les conflits susceptibles de survenir entre l’auteur d’une œuvre et le propriétaire du support », Ing.-Cons., 2004/2, p. 91, STRADALEX.

The purpose of copyright is to provide a sequential solution to the contradiction between financing authors and free access to works. The establishment of copyright aims at making the work of the mind exclusive, by granting the author a monopoly of exploitation on his discovery.

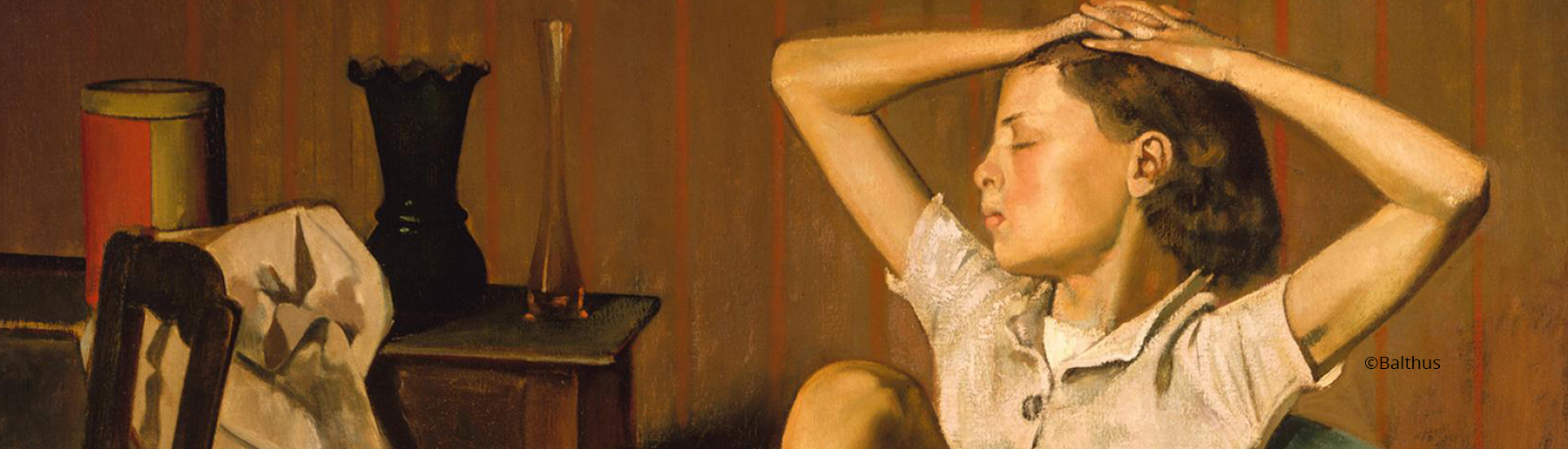

“Since always, the artist is in the vanguard of the “becoming-oneself”; he chooses a destiny that nobody could choose for him. More than any other, he escapes from routine, dares to become himself. It would be fascinating to tell the story of the birth of the vocation of the great creators. Unfortunately, we will never know anything about the vocation of the painters of Lascaux, the sculptor of the so mysterious Olmec heads, the author of the book of Job, Homer (if he existed) or the creator of the sublime bust of Jayavarman VII.

Attali, Jacques. Devenir soi (Documents) (French Edition) (p. 55). Fayard. Kindle Edition. “

Read: Copyright.